How many times does the average teacher ask students to “take notes” in the course of a semester? Daily would be reasonable. In some instances, it may happen multiple times in one class, if annotating different documents for different parts of the lesson. Like the vast majority of edTech tool instructions, “take notes” is overused, under-instructed, and often misinterpreted.

What are “notes”?

Fundamentally, notes are a capture method for students in the process of learning. Their notes may capture teacher comments, video elements, or text items from pages they read. Notes are the formative stage of internalizing academic information. However, is note-taking in sync with modern classroom developments, like digital texts, online documents, and digital storage?

At one time, notes were taken because students did not own the academic texts from which they studied in the great libraries. They would open the book from the dusty library shelves, read through it, and copy the salient points onto loose pages or into notebooks that they could take with them. When students don’t own their textbooks, they would be disciplined for writing in them. In a digital age where a personal copy of the text is possible, is traditional note-taking necessary? Most certainly, it is.

Note-taking as a Process for Digesting Text

Imagine a text like a plate of food. A chicken breast, a potato, or a carrot must be prepared so that it is palatable. That cooking, some trimming, and flavor-enhancing is much like the authorship process through which texts are presented to readers. However, the plate, the utensils, and perhaps other presentation items, like the foil wrapping a potato, are not intended for consumption. Readers select the succulent morsels which they want to internalize. Some text will be left behind. Notes, with a pencil, stylus, or keyboard, are the edible pieces which are captured in the eating process. Separating the good food from the rest is like underlining, possibly highlighting. Yet a plate of trimmed food isn’t enough; it must be cut to bite-size pieces before it can be eaten. Extracting content to margin notes is helpful. Savoring the food requires chewing in order to break it down and reorganize it to prepare it for digestion in the stomach. Customized notes, which are written in one’s own words and possibly presented in a graphic format like a Venn diagram, list, or spreadsheet, are the essentials which keep students from starving from a lack of internalized information.

The Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve (click here) states that retention of information declines exponentially over time when it is divided by the strength of a memory. In short, humans forget all but a tiny fraction of their memories within a day. If educators want to impact retention of content, they must enhance the strength of the memories.

Some will say that students do not internalize information until they have written it with their own hand. This is based on some out-dated research which was fraught with complications that became clearer over time and replication. Yes, students learn when they write notes, with a pencil or pen. They also learn when they write them with a digital stylus or when they type them. Rocketbooks (click here) can be a solution to bridge this gap because they function like a standard paper notebook with a pen, but can be digitized for cataloging, archiving, sharing and for transcription from hand-written pages to typed text in seconds. OneNote Class Notebook allows students to write with a stylus or type on a digital page (even a customized graphic organizer or prepared worksheet), just like they would on paper.

Students who copy notes forget them only slightly less than just having read them. They do not have to engage their brainpower significantly to copy the words of another person, whether those are typed or handwritten, as on a whiteboard. Much like the meal previously described, students internalize the content when they read it and write its essence in their own words, using their own organizational patterns. The frustrating thing for teachers is that the “magic” of their own organization patterns is locked within the individual. However, what teachers can do is provide examples of organization patterns which might be helpful, so that students compile a personal “bag of tricks” which fits their own cognitive needs. In the absence of such instruction, the default to what they have seen from a prior teacher or other students — likely highlighting and underlining. For an excellent breakdown of methods (click here) read this post by Sander Tamm, although he leaves out sketch-noting which can be highly effective with visual learners.

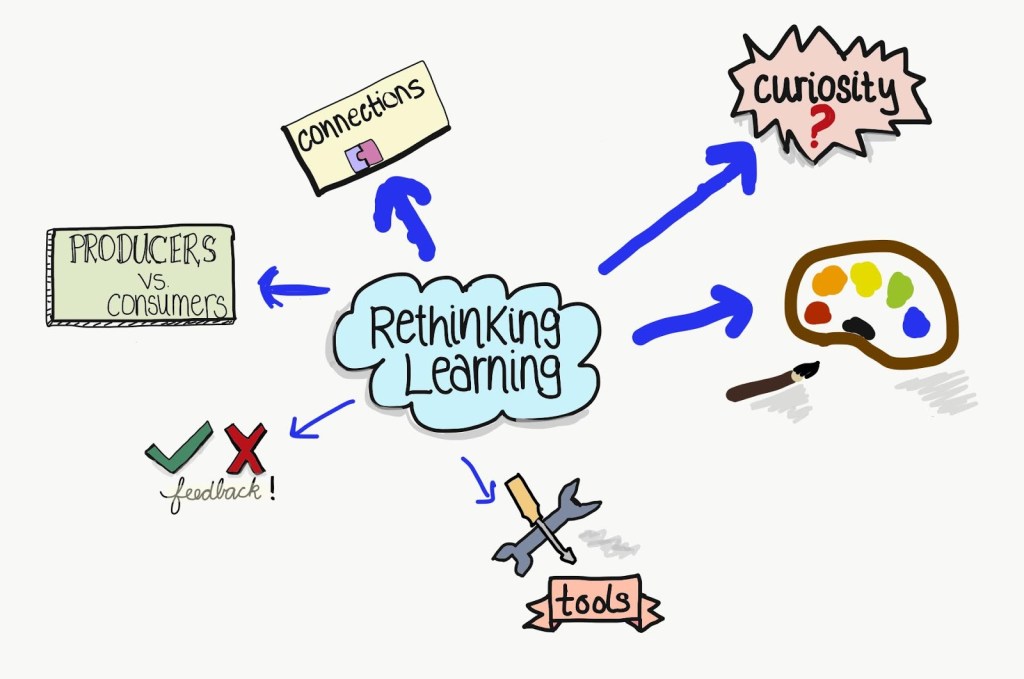

No single method is the “secret sauce” for all students, but that doesn’t mean they can’t benefit from learning about each one. Instead of telling students to take notes, consider suggesting they try a particular method to learn about varieties of note-taking and give them the freedom to revert to their own method, if they prefer it after trying this suggestion. Certain methods are preferred for different types of content. Sketch-noting or mind-mapping makes a lot of sense for concepts. Details and facts are often well-represented in an outline or list. Comparative elements gain value from the juxtaposition of a Venn diagram or a spreadsheet. Any method by which students recreate the content learned in their own words or recognizable and translatable symbols gains that strength of memory over simple reading and attempting to remember.

Personal Testimonial: 10 years of U.S. History and OneNote

Note-taking is an important element in my curriculum for U.S. History with 8th grade students who will be transitioning to high school at the end of the year. I have begun sharing my observations about student note-taking practices with my students at the outset of the school year. As a paperless teacher, I have ten years of evidence to support the following observations because my students take class notes in OneNote Class Notebook, which I can see through my teacher interface. On occasion, I have also shown parents that their child who “didn’t score well on the test, but took notes and studied” actually didn’t have decent notes, supported by a few clicks into the student notebook on the assigned text pages. I can also show other students the power of excellent notes with a variety of examples (deidentified, of course) from OneNote.

- Some students read a text and highlight passages on the page. If they do nothing more than highlighting a text, I have noticed that these students generally score a D on the traditional test of the material. I also noticed that some students fake highlighting so that it looks like they are working, but when you read what they have marked, it is gibberish instead of key items.

- More students mark the text, using underlines instead of highlights. They sometimes have systems of double-underlines for people, circling of dates, and boxing definitions. While it’s less likely that they are faking the work, it can be more like a scavenger hunt on the page — “Oh, numbers — must circle,” instead of recognizing the relationship of that number in context. In general, these students scored a C on the unit test.

- When students go beyond the text and extract information to write it in the margin in their own words, they must hold it in their brains at least long enough to do so and it is in their own language for easier studying and recognition. This is the minimal level of notes that I consider acceptable. Studying from them is much easier. Students who take this step tend to score a B or better on the test.

- When students jettison the text and write their notes on a separate page which is entirely meaningful to them, they empower their study habits. Sure, a vocab practice in an app or on notecards can be helpful, but reading your own powerful notes with outlines or graphic representations of the key data speaks to their brains like no academic text can. They hear their own words and see the orientations on the page. These students, as you may have guessed, set themselves up for an A.

It’s all based on the level of interaction and digestion of the material. Pardon the example, but regurgitation is a poor substitute for the original and swallowing food whole is problematic. Why would we allow students to apply the same strategies for course content apprehension?

Teacher Takeaways

The value of notes for academic success rises in direct relationship to the level of interaction and personal translation of the content in creating them. Digital solutions abound for note-taking success.

Tamm, S. What is the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve? e-student.org. 13 Feb 2023.