Executive Function Series – Part 6, inspired by The X Factor: Executive Function Tools in Google (2023)

When beginning a semester or my weeklong summer camp on executive function (appropriately called EmpowerEd Camp), I spend time talking with students/campers about who is in charge. You may be surprised to know that I emphasize that it’s not me….it’s them. For most learners, it’s the first time in their lives that they have ever heard that from a teacher or adult. It disarms them — and it empowers them.

Quite simply, I provide opportunities to learn and stretch themselves and their knowledge base, but everything else is up to them. In class, we begin by making an agreement:

- I provide the learning resources that they need to get background on the course topic.

- They acknowledge that they do not have the choice to skip a summative assessment but every other choice about their learning is up to them.

In camp, I provide the structure to keep them going on the same goal for three hours a day and they recognize that they can choose to learn anything with me for a week — a self-driven camp.

Students in charge of their own learning? !

That seems crazy to many people. I would argue that asking a sentient human being to be entirely subservient to someone else’s will is far crazier. Children can achieve many and marvelous things when adults foster them by modeling and guiding them in the structure and resources to make success possible. Previous segments of this series have addressed GMail for Google access and effective communication and Google Calendar for scheduling. We turned last week (click here) to Google Tasks for operational organization.

Dr. Sucheta Kamath, Executive Director of ExQ, defines executive function as “getting the ‘boss’ brain and the ‘worker’ brain working together.” With some help, students can learn to coordinate the needs of their ‘boss’ brain and their ‘worker’ brain effectively, but it doesn’t happen in a vacuum. They need tools — like Google Tasks. They also need to hone the habits to utilize it well and to lean on it for the support that it can offer in areas where they may be weak — like completion and prioritization. These are the exceptional deliverables of Google Tasks.

For more depth in accessing Google Tasks, check out last week’s post in this series (click here) which focuses on the intersection between Google Tasks and the needs of teachers. This week is dedicated to methods for encouraging learners to incorporate Google Tasks in their daily habits. Of course, this is easiest in a one-to-one school environment where the computer is available during each class session, but it can work just as easily with phone access. To be honest, one of the greatest impacts of this tool is the fact that it can be anywhere that the student has access to log into Google — school, phone, home, Grandma’s house, or work. If students only used it at school, it would have little value.

Modeling Organization and Agenda-Setting

Google Tasks is best demonstrated through modeling. Whether you write the same kind of detailed plans that were part of the teacher education courses you took to get certified or join the other 99% of us who do not, every teacher has an agenda of some sort for the day’s lesson. Mine are written in an assignment block on our LMS and in a one-line version on our digital bulletin board for the week’s lessons. I also write them on the whiteboard in the classroom so that they are visible to students during the entire class period and they know what to expect. A sample day would look something like this:

- Essential Question: How did the Northwest Ordinance transform America?

- Current Events Check-in

- Homework Check-in

- Task 1: Reading Land of Hope, Chapter 7, pp. 59 (para. 3) – 63, aloud

- Task 2: iCivics.org “We’re Free; Let’s Grow” activity, completion with small group contacts

- Task 3: Large group discussion “The Northwest Ordinance and Post-War Economics”

- Task 4: Design your own graphic organizer to show:

- Conditions of the Northwest Ordinance (1787)

- Changes in the Ordinance of 1790 (southwest)

- Land Ordinance of 1795 (where, why, $$)

- Land Ordinance of 1800 (where, why, $$)

- Homework: Save iCivics pages to OneNote for studying and finish the graphic organizer for partner-share feedback. NOTE: These are study guides for the test next Wednesday.

Granted, our classes are 80 minutes long. Making a point of referring to the task list on the board as we transition through our classroom activities provides a refocusing on the goal, an acknowledgement of the list to be completed, and a theoretical checkmark on each of the items as it is completed. They know that all of those tasks must be completed in our time together because they would not be able to complete the 4th task without the work that we do together, except with a lot of extra study and time-consuming research on their own.

While they are on the computer for iCivics, students can take a moment to add the two homework tasks to their running list in Google Tasks. They simply click the icon from a saved bookmark in the browser OR from the right side of the GMail screen (or other Google apps) OR from the Google “waffle” of nine squares in the upper right corner of most apps and the browser. Then, click the plus (+) sign to add a task and type “Save iCivics We’re Free, Let’s Grow to OneNote” and set the due date for today. Another click of the plus sign will add a task to “Finish Land Ordinances Graphic Organizer” by the date and time of the next class period.

That’s the novice or JV version. The varsity step is to add a time over the next week to spend 10 to 15 minutes studying each of the items twice before the test next Wednesday. A few students would do this automatically, but it takes a reminder or two from the teacher as students complete each of these items in class that the “pro tip” is to add time to study them before the test. A mid-class mention and one in the last few minutes when students are packing up and updating their homework lists should result in adherence from about 90% of the class. Of course, this builds over time during the semester.

It’s About Time!

One of the dirty, little secrets of phone or email scams is creating the sense of urgency (like a limited time offer) which impels individuals to meet the deadline and to actually feel driven to do so. Why not assist students to use the same strategy for completing homework?

Anyone can make a list — on paper, on a hand, in a planner — but Google Tasks does it better by adding the time-sensitive feature. To-do items are easier to procrastinate when they don’t have a concrete completion time. In Google Tasks, dated items are prioritized at the top of the list and undated items slip to the bottom. When students get in the habit of adding today’s homework with the date and time of the next class as the due date, it creates an automatically prioritized list based on urgency.

Where Are Your Priorities?

Once students are in a habit of adding completion dates to their tasks, teachers might coach them to attend to and anticipate the time it takes to complete items. For example, they might add a parenthetical code to tasks suggesting how much time to allot for them. This certainly takes time to develop with any accuracy. One step is to add time blocks to the schedule for the daily lesson and mention it when you meet or exceed those times. This can help learners to recognize that a task like “Write a persuasive paper” and “Read three pages in history text” are not equal. Two strategies come into play in this circumstance.

Strategy 1: Coach students to plan tasks in blocks of 15-20 minutes completion time. This can connect fairly well with the Pomadoro method of working for 25 minutes and taking a 5-minute break before settling back to work. In this instance, the paper might be broken into multiple steps or “bite-sized” chunks such as outline the persuasive paper, draft body paragraphs, write introduction and conclusion, revise paper, and proofread/submit paper. Much like the process of packing, it works better when things are generally the same size. Odd sizes waste space and huge tasks can lead to wasted time.

Strategy 2: If students aren’t in the bite-sized mode, another option is to learn to motivate themselves through incentives. Incentives can be anything — a snack, a break, a run, one level on a game, a nap, texting or calling a friend. Tasks can create a bargaining opportunity for them. In Google Tasks, students can click the star to the right of a task to mark it as a special thing (like “bonus points”). “If I do this big thing, I get this big incentive. I would have to do three other tasks to get the same perk.” Another option is that specific incentives must wait until all tasks for the day are completed. In that scenario, procrastinating means not gaming tonight. Of course, young people have to build the strength to hold themselves to these guidelines.

Supporting Success and Providing Pointers for Pitfalls

In either case, parents can help by supporting noble goals. Instead of asking if the homework is done, it’s better to ask about accomplishments. When they see a break happening, asking how the child earned the incentive reinforces individual accountability, instead of hard-core external consequences for infractions.

For teachers, the reinforcements can be subtle, supportive comments about on-time work and good attention to detail. They can also involve some crisis management. Looking over a child’s shoulder when they are adding to their homework list can be an opportunity to mention to add the date and time. If a student seems to be managing their own schedule poorly and a teacher has time for a brief conference, remember that the arrow at the bottom of the page in Google Tasks shows the completed items. A quick review of these old entries can show how much or how little is being added to the to-do list, so that suggestions can be made for improvements.

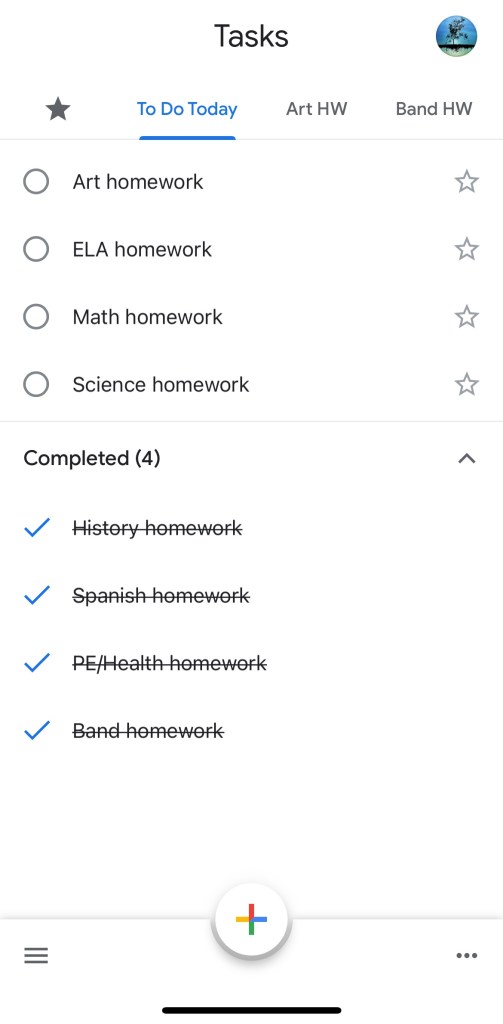

Organization of the task list can impact learners differently. By the end of the school day, there may be a very long list, which can be daunting and create an unintended obstacle. For students who struggle with longer lists, remind them that it is possible to create separate lists, so they can have one for each class. When using this method, it’s wise to have a main list which has some common reminders (see image below). This can actually be a short list which references each of the other lists. In this case, the standard classes should all be listed. If they have been completed on prior days, they will show up in the Completed Tasks section at the bottom of the page. They can be unchecked to return them to the list for attention. This works like a toggle switch, either on or off, so students can prioritize which classes must be completed tonight.

Realistically, Google Tasks is a very basic app to use. Users add items and check them as completed. It allows customization with multiple lists, favorites, and date/time features. In the end, it’s still a list. Lists and items cannot be shared or searched. While completed tasks are still available, they don’t provide an effective archive. For those features, check back next week for an exploration of Google Keep, recognizing that each tool has a purpose and that sometimes simple is a beautiful thing.

Teacher Takeaways

While teaching students a Google tool like Tasks isn’t in the curriculum, guiding learners to manage their homework agenda better saves teachers considerable time in the area of addressing missed and late work.

References

Kamath, S. (2022-11-21). “Can strengthening executive function help us be our best selves?” TEDxAtlantaWomen. YouTube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TYtXqO_Uy9c

One thought on “Improving Executive Function with Google Tasks (for Students)”