Thanks for checking in again for the “flip side” of last week’s conversation (click here) focused on using Google Calendar as a teacher to visually experience your work schedule, see windows of opportunity for meetings and tasks, designate planning time to improve productivity, and set boundaries so that work time and personal time are discrete from one another.

How much of those crucial planning elements and takeaways are transferrable to students? Honestly, their story is different — and there really isn’t one story for all students. For me, a realization occurred when I heard from a student whom I passed in the hallway when I arrived at school, that they were dropped off early when their parent was on the way to work. After working an hour or so after school to grade assignments which didn’t get done during the day, I saw her working on homework at a table in the student center. The next day, I heard about an 8:00 game and that she didn’t get home until 10:30 PM. Prior to that experience, I saw students through the lens of the school day (7:45 AM – 2:45 PM). Her day didn’t start at 7:45. It started at 6:30 AM, when she left home so that her parent could be in the office at 7:00. She did homework after school (or did she?) before practice started at 5:00 PM. When there was a game, it was an evening game, sometimes the second of the night for the gym, and after post-game activities and the commute home, 10:30 PM was the walk-in-the-door time. I’ve had students who played hockey and regularly had ice times at 9 or 10 at night. Performers in the school play have long and late schedules, too. It’s not just sports.

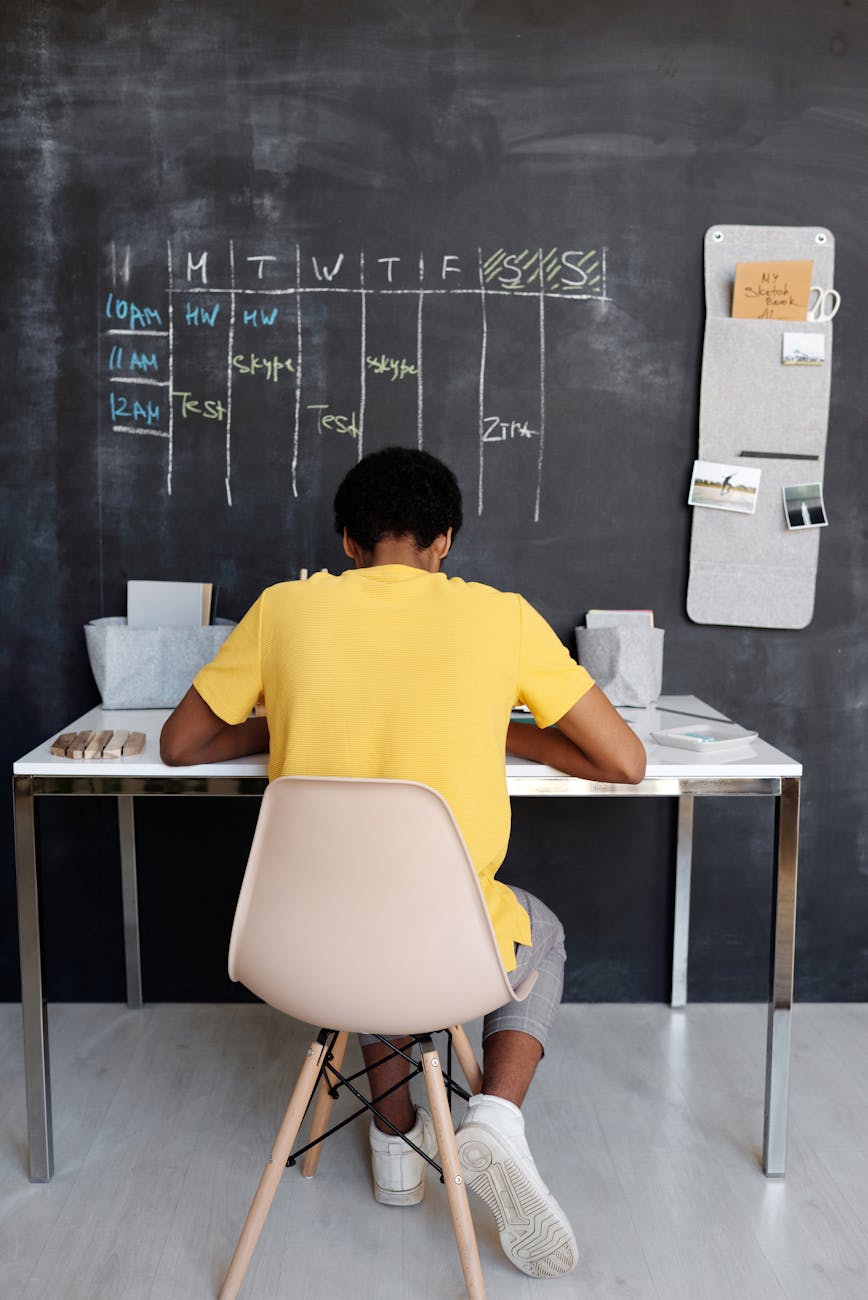

School is one of many things in the day. If students aren’t equipped with efficient and reliable methods for managing the demands of homework, it will fall by the wayside.

You can help students by encouraging the use of a Google Calendar for homework. The benefit of Google Calendar is that it is accessible from a computer or phone, so they don’t have to remember a notebook planner or be lost without the information if it is forgotten at school. First, familiarize them with the idea that they can view many calendars simultaneously. Keeping the school-provided calendar linked to their own view is very helpful for adjusted schedule days and semester breaks. Instructions for “subscribing” to a calendar (no commitment involved) are provided at this link (click here). Adding a family calendar, if one exists, or a team calendar are also helpful to see the layers of commitments and events at the same time, without having to enter the data manually.

The next step is creating their own calendar. This can be the default calendar for their GMail account or it can be a custom-created one, such as “My Homework Calendar” to keep homework separate from other activities — and perhaps share it with parents so that they are aware of the workload of being a student today and can be aware of tests, papers, and projects so that they can offer support or just bandwidth for the extra time those activities involve.

“Due” and “Do”

An honest conversation about these two words is a good step in learning about calendars.

- Due refers to the deadline for completion of the work. For some teachers, this may be a severe date with penalties for non-submission of the assignment. Other teachers may be more flexible, but that usually comes with the fact that other assignments are likely to overlap the days that follow a due date.

- Do refers to the date/time when the action is completed. This may be a short timeframe, like 20 minutes in the evening to work on math problems, or half an hour on three successive nights to study for an upcoming test.

There is value in calendaring both perspectives, but they should be made distinct. For example:

- September 25 at 10 AM event reads: DUE – Triangular Trade Essay (World History)

- September 21 at 4:30 PM event (15 minutes) reads: DO – Outline Triangular Trade Essay (World History)

- September 22 at 4:00 PM event (45 minutes) reads: DO – Draft Triangular Trade Essay (World History)

- September 23 at 4:00 PM event (30 minutes) reads: DO – Revise and proofread Triangular Trade Essay (World History)

Guiding Expectations for the Schedule

I smile as I think of an “old-school” family friend whose adage was “If you’re not ten minutes early, you’re late.” Students don’t work that way; sometimes I don’t either, though I try. Talking with students about what that calendared time really means is important. Give examples that are clear and present in your classroom. When the bell rings, procedures begin. If an activity is supposed to take 20 minutes of the class period and runs long because of deeper conversation, I am apt to look at the agenda for the day on the whiteboard and direct students that, in order to respect their time, Task 4 is something that we can probably do a little differently to get done in less time or could be skipped. That demonstrates time management within the classroom. They (and administrators) certainly don’t appreciate situations when class extends beyond the dismissal bell. They know that calendar times should be exact, not flow over at the end like a waterfall.

Avoid assuming that students should know how to conduct themselves during homework time because they have been doing it for years. Written work requires a table. Creative work requires supplies. Digital work depends upon a charged and functional device. Everything, including the mindset, an empty bladder, and a glass of water, if necessary, should be in the homework space. My personal opinion is that a cell phone should not be in a homework space, with the exception of when it is used as a resource — assuming that the distraction features and notifications don’t become an impediment.

Setting Boundaries

Returning to the essay example — What if the essay has not been completely written by the end of 45 minutes on 9/22? This is a question to ask students when discussing calendar management with them. We know that this is a potential problem, so we need to help them manage what to do. Consider a dialogue with a flow chart graphic on the board to show the following options:

- “Keep working longer”

- Check the calendar for a window of time at 4:45 PM

- If another activity is scheduled, can it be shifted slightly later, rescheduled for another time, or cancelled?

- Would continuing to work result in more fatigue and inefficient progress? Would it be better to return to it after dinner or practice?

- Adjust the calendar event for a fixed amount of additional time or add a new calendar event for the follow-up work time. (Why? The calendar should reflect actual use of time. Adjusting demonstrates the visual of the real situation, not projections. Memory of the adjustment could suggest that 60 minutes is needed for the next homework time to draft an essay.)

- Notify others who may be impacted by the shifts.

- Complete the work within the window provided.

- Reflect on steps in the drafting process which could have improved the use of time — responding to a text from a friend, stopping to use the bathroom for ten minutes, staring at your trophy from last season and thinking about baseball instead. These are fixable.

- Check the calendar for a window of time at 4:45 PM

- “Work on it tomorrow instead of revising. Aren’t they the same?”

- Check the calendar for extra time tomorrow following the schedule time.

- Recognize that drafting and revising shouldn’t be done at the same time. Separating from the written work gives a fresh perspective which can help improve the final product.

- No, they are not the same. Consider skipping a step in tying shoelaces and see if the end result is satisfactory or flawed.

- Adjust the calendar event for both days to reflect actual use of time.

- Notify others who might be impacted by the additional homework time tomorrow.

- Honor the commitment to complete the work in the adjusted time allowed.

- Check the calendar for extra time tomorrow following the schedule time.

- “Take an extra day and turn it in late, but better and complete.”

- Again, analyze the consequences. If underdeveloped essays could drop the grade 20 points, but late work is either not accepted or immediately drops the grade by 20 points, the penalty is likely to be worse than a poor assignment.

- Check the calendar

- Is there any window of time which could be used or adjusted to avoid a late assignment?

- Lunch time — make it quick and head to the library to work the rest of the time.

- Study hall

- Getting up early and working before leaving for school

- Asking permission to do a Wednesday chore on Saturday for extra homework time.

- Forego a “want to” event in order to complete a “must do” event.

- Is there any window of time which could be used or adjusted to avoid a late assignment?

Set the Scope

Start small for students because these things can be overwhelming. For example, set up a single week. Some students will be surprised by how much they have in their schedule; others may be surprised about how many places they have “windows of opportunity” in their schedules that they don’t utilize well.

When I talked to my history students about vocabulary and taking 15 minutes per day for practice, they struggled. When I asked how long the bus ride was or the car commute, most were at least 20 minutes. They quickly realized that they could use Quizlet on their phones to practice vocab will commuting and eliminate a block of practice time. This was a win for everyone.

At the end of the trial week, talk about some of the observations and strategies. Next, ask them to consider how many of their events could fit a regular schedule. Realistically, 15 minutes per day per class can be done in a two-hour block with breaks and a buffer for extensions. If students follow a block schedule, they might be better able to schedule 20-30 minutes for each course from the day to complete the work ahead of time with the next day as a buffer. The bonus with a routine homework block is that the calendar blocks can be set up as “recurring events” (click here for instructions). For example, a 3 PM-5 PM two-hour block could be set up for four, 30-minute blocks of time daily. If first period homework only takes 15 minutes, there is time for a break before Period 2 at 3:30 or each block could move for an extended block of “free time” at the end, assuming that another block didn’t need extra time.

Just being able to see the time spent will result in realizations for students. Of course, they won’t be experts at the practice in a week, but it will help them over time to be realistic about scheduling and being more efficient about their work.

PRO TIP: If you happen to schedule your class on Google Calendar and have shared that with students, it is a simple step for them to copy an assignment to their homework calendar instead of adding the “DUE” post above. If you have the details, resources, and requirements in the description section of the event, and perhaps a link to the rubric, they will have all of the same information for reference. Think about the impact on the final product and the time saved for them! To copy an event from your calendar to their own, students can click the event, click the More icon (three dots), and specify that they want to copy it to their “My Homework Calendar.” This does not change your content or grant them access. They simply have a copy of it.

Teacher Takeaways

A digital calendar, which can be adjusted, helps learners to visualize the abstract concept of time and manage it efficiently.

One thought on “Improving Executive Function with Google Calendar (for Students)”